View video interview here: http://www.collaborativesociety.org/2016/04/05/charles-leadbeater/

Different modes of Collaboration and Leadbeater's Book "We-Think"

Why Did You Call the Book "We Think"?

Do you want the real answer? So the real answer is I can't tell you how many titles we tried. I wanted to call it "We Are What We Share" and the publisher said "no, you can't do that." I wanted to call it "The Power of Us" and then the publisher said "no, people will think that's about the U.S." We tried various things, at one stage I called it "The Barefoot Manifesto," that wasn't right because it wasn't right. We went through various things and then it was when I was thinking about Descartes and "I think therefore I am" and was actually on holiday with my family and with my wife's sister, my sister-in-law, and I was discussing it over breakfast with her and she said "why don't you call it not 'I think therefore I am' but 'We think therefore we are'" and that's where it came from.

The Greatest Problem for Our Educational System?

The first problem is that we're going to need entirely new solutions because we now have an economic model which millions of more people every year want to be part of but which is unsustainable, environmentally and in some sense economically. It can't sustain itself. Capitalism is both hugely productive and deeply unstable and very creative and yet very destructive all at the same time. And we're going to need new approaches to water, to energy, to transport, to housing, to heating. We're going to need new solutions to lots of these very fundamental things and so I see if the education system isn't creating the culture and capabilities of people to solve problems of that kind, that's a big problem. So that would be the first thing I would say.

Those are problems which will require innovation, creativity, challenge, questioning, imagination, all sorts of characteristics, courage. And I think that we need a education system which secondly prepares people to be governors, with other people, of their own lives. So in a world in which the most important level of governance is really how we govern with one another, rather than government governing us, and how we create a more integrated and inclusive society rather than a deeply unequal one. And so these are the three big challenges I think.

Going a Bit Deeper With the Challenge of How to Create a New Culture of Learning

So I think most innovation in education is attempting to improve what we've got and improving what we've got is school, teacher, class, lesson, timetable, instruction, exam, so on and so forth. And I think there are some people who are trying to sort of reinvent school by trying to break it down and make it more collaborative and personalized and those are very interesting examples. But I think that the most disruptive ways are going to go in two completely different sorts of directions. One is that I think if education makes the mistake of allowing people or encouraging people to think that the point of education is to get qualifications and exams so it's all about what you come out with then I think it's absolutely obvious that people will think we'll just do that in the most efficient way possible because what I'm interested in is the outcome and so then I can't imagine why in ten years' time kids are not going to think "I'll just go onto Spotify and find the best course to teach me how to get through this exam and I'll learn it from this teacher or this program and maybe I can find a group that's doing it together" or some version of that. So that would be radical and disruptive but it would be very limited I suppose in its goal.

So more interesting will be can you create forms of more radical and disruptive but more collaborative and exploratory and creative forms of learning which will be both online and offline I suppose both in the real world so that that would be not just using technology to do existing job, get through exams more efficiently, but using technology to create new kinds of learning which have at their heart, asking interesting questions, exploring uncertainty, trying to create solutions not just learn answers, working collaboratively, doing things with your head and your hands, so on and so forth. That I think is a kind of mixture of the very new technology and, in a way, kind of very old things about learning. So I think that that's some of the most interesting areas.

People, of course, emerging from education want to and need to be able to show what they've got from it and we have got into a situation where we associate the outcomes of education with the exams that we get and actually they of course matter because they matter which next stage in the education system you're going to and those might determine which kinds of professional qualifications you get and which kind of job you get and income and so on and so forth. So all of this matters a lot but actually whether we're wealthy, whether we're happy or indeed successful or able to cope with life or a contributor has to do with all sorts of skills: can we collaborate, can we communicate, are we a problem-solver, do we recognize the skills of other people, all these kinds of things and actually in a lot of settings the exams we learn have no use or relevance or bearing or meaning compared to the problems that we might need to solve or the issues, challenges that face us. So in that sense the more useful kind of education might be practical, vocational, creative, productive.

An Example

I was in Sao Paulo, Brazil and I went to a house in the suburbs of Sao Paulo which has been taken over by a community of kind of cultural entrepreneurs and hackers who have created a remarkable platform in Sao Paulo, in all of Brazil, called Fuera de Eso which is "outside the lines." And this started out of the crisis of the independent music sector. So when the independent record labels and other record labels kind of were hit by the Internet, bands lost their way to market and so in that space lots of independent music festivals grew up all over Brazil and then they started coming together. And this group, Fuera de Eso, grew out of that collaboration between these festivals so how could they support one another. The group in Sao Paulo, the center of it, they live and work together so part of the deal is you work but you can live in the house and feed one another. So it's almost like a commune, it's almost like something from Berkeley from the 1960's.

So they literally live and work together. And it's very interesting in the house because it's kind of like hippy-ish, but they're working really hard and they're very, very focused and they take what they do very seriously but it's very alternative. So there are now 50 of these houses all over Brazil and there are 200 cities involved and they put on 6,000 events last year. And in order to organize it, they created a trading system, so they have their own currency that they trade within this network. And in order to get people into it, they have a kind of university that they run courses. And it's almost like a political party. And so it's an absolutely remarkable kind of platform for creative, collaborative, free culture with its own trading system, its own university, its own sort of ideology, I suppose. And which came out of a mixture of crisis but also a kind of culture of Brazil and the kind of improvisational, do-it-together kind of culture.

And I thought that was really interesting. That that had come from Brazil and from crisis and out of music. That new possibility. They have a couch-surfing bit to what they do and they had, I think, provided 15,000 beds last year. So this is like a kind of entire little ecosystem of value and ideas and culture and work that came from absolutely nothing. So they use Facebook, Twitter, Google Docs, Skype, so on and so forth.

We Are On Edge Of. . .

I think we're on the edge of two really big things. I mean actually I think we're in collaborative science now. I think all science. I think science at its root is collaborative. As Heisenberg said, "science is conversation, really." So most big scientific breakthroughs came from collaborative environments that were highly conversational and quite open and quite sort of freewheeling I suppose. But what the web and massive data and open source programs and free and open publishing and all of that what that has created I think means that basically all science is now highly collaborative, it's only a question of how collaborative, who collaborates, how long, where, for what purpose and so I don't think you'd start science now, I think if you looked at young scientists they would be, in their instincts, collaborative. They'd start with open source repositories, they'd use open source programs, they would communicate through social media and other ways, they would publish in open journals and so on and so forth. So I think the question is where the collaboration might go. And so site, another ah-ha moment, not ah-ha but really inspiring is Zooniverse, which is the citizen science site doing citizen science. That whole notion of citizen science, you could do citizen social science and so on and so forth.

So that's one thing, and the second thing of course where we are on the verge of is the interaction of technology and humanity, people and machines in which synthetic biology and the disappearance of technology into people will become more and more common I suspect. So in that sense I think that will be huge but then also, I suspect, that the principles of biological innovation, evolutionary innovation, will become more and more important to industrial and commercial innovation. I hope we will look to biological models in which there's no waste, that waste is fuel, that systems are designed to sustain themselves rather than to consume resources. That those kinds of biomimetic principles will become really important.

But I think that if you want one of the kind of questions about the Internet I guess is if you look at the characteristics of mature ecologies which don't require the constant consumption of additional resources to keep them going but are in some sense self-sustaining that is I think one of the design challenges. And so I think the big design challenge for business is how you adopt, if you like, circular models in which nothing gets wasted. Everything gets used and reused and in which you probably kind of get very skilled at reusing things and using local resources. Those are the kind of the design principles I suspect we're going to need if we're going to have any chance of living within kind of environmental limits.

Motivations for Collaboration in Different Social Ecosystems

They need a mixture of being part of something bigger and wanting to be part of something bigger. Because they feel by being part of something bigger they get more meaning I suppose in their lives or to their activity and also that they personally get something from it that is rewarding in some very broad sense, not materially rewarding but rewards their sense of identity or solves a problem for them or simply that finds a community within which they can kind of talk and find and identity I suppose. I would say that those are the kind of two main things but you're absolutely right that the critical issue is why would people do it and not how or the mechanisms but what's the motive that keeps people coming back and wanting to contribute.

The really interesting and problematic thing is that if no value gets created unless people are prepared to share it and to share it, they need to share it because they need to collaborate, so to create value you need to share it and collaborate who sets the terms for that collaboration because then of course if the terms for all of that is being set by Apple or Amazon or Google or Facebook who are interested in you sharing more because actually each time you share more they make more money but you don't get very much out of it. This is a very sort of unequal exchange and so the question is whether you can get different ways of creating that kind of cycle and I think that that is part of what people are looking for I suppose. I mean I think people are kind of prepared to be in forms of collaboration where they get enough from it and they're not too concerned but if they feel that disproportionate rewards are going to other people without them getting something back they may feel it's unfair. And there's lots and lots of work about collaboration that shows that if cooperation offends a norm of fairness then it starts to break down. I think that we're at a very early stage and I think that people are so still finding their way with the Internet and the models it's creating.

So on the one hand it appears that we can share and get things for free: Wikipedia, open source, stuff like that. Actually you don't have to pay anything and you get lots as a consumer. So in one sense there are lots of companies that say it's just a transfer of value to consumers because consumers are getting something free. Then on the other hand if you exist in the Apple ecosystem which lots of people do, like us, then you're constantly paying Apple.

Which Structure is Needed in the Collaborative Process?

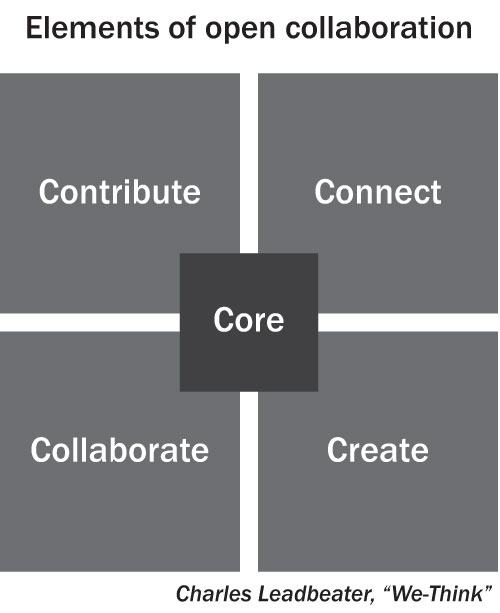

So I would say looking at the kind of collaborative projects I looked at -- Wikipedia, open source, collaborative science, other kinds of things which don't necessarily involve the Internet -- that it's very difficult for people to start collaborating without some core that someone has put in place that says "look, I've got something which is promising but unfinished and could other people contribute to it." So then the second thing you have to do is both create a way for people to contribute so it's appropriate to them, it's easy for them to do, it's not too onerous, it's appropriate to their level of skill and technology. But also that they want to contribute so there has to be a kind of reason for that, a cause or a purpose or a problem that they're solving. So you have to create a core, create a mechanism and a motivation for people to contribute then find ways for people to start connecting, not just with the core but with one another so that then so that the third thing is can you connect people so then the fourth thing is can they collaborate so not just connect but start doing things together.

Now sometimes people can cooperate without collaborating because they just do "you do that task, he'll do that task, we don't need to really get together." But actually I think these things really take off when people do start to connect and then collaborate even if for a brief period. And for that you need some mechanism of governance so that people agree on some rules or some general norms about how they're going to resolve arguments or make decisions because one of the reasons collaboration breaks down is that no one can ever agree and everyone always talks and nothing ever gets done. So one of the reasons why communes and cooperatives break down is that they become inefficient and inward-looking and so they need to become effective at making decisions which is why they need a mechanism of governance and the governance mechanism needs to have some structured way of making decisions then you can create things. And out of that comes then this sort of positive reinforcement that you're actually generating something, it's growing and people are adding to it and so on and so forth.

Now often you can get some of that but not all of it. Sometimes you can get it started and then it sort of dribbles away. There are lots of examples where people put up a core but no one will be interested in it so it's dead, open but dead. It's open but really no one wants to contribute. And designing all of that is a constant process of learning, testing, readjusting, trying to kind of connect with things beyond you. I think the really important thing is that it needs to sort of have this sense that it's always trying to connect slightly beyond itself. It's not just internally, it's trying to find new things to do, new problems to solve, new people to contribute in some sense. And so then this notion that you also need then to credit people, that people need some sense of reward or recognition, most importantly recognition really which will come in all sorts of forms and that they get something back from that.

It becomes then a sort of generative thing. It is a form of trust I suppose, faith. That actually if you put something into it there's a form of reciprocity involved that if you put something in you will get something back and it might be via some quite indirect route. But you'll get something back and quite probably you might get back more than you put in. But you have to trust, it's the sort of faith in generosity.

Which Personal Virtues Have You Seen in Play in Successful Collaboration?

A mixture of generosity, "I'm going to give this to you and I'm not expecting anything back in exchange although hopefully at some point I will benefit from this but I'm going to" so it's sort of generosity, a trust, of "pay it forward" that "if I put this in other people are more likely to contribute and then we'll all get something bigger." And so in that sense a kind of certain act of faith in other people, showing your faith in other people and through that encouraging them to reciprocate.

The other thing I suppose I would say is the thing that I notice about the people who are very good at encouraging people to take part is that they are "charismatic by being humble" is how I put it. So they are deeply, deeply charismatic but they are charismatic because they recognize their own limitations and so they create space for other people to contribute. So they do not want to occupy all of the space. They're not deeply egotistical. They have a certain sense of security about themselves which allows them to recognize the limits of what they can do which then means they are extremely good at recognizing the contributions of others. Because if you set something up and you're not interested in the contribution of others, they won't contribute. So you've got to be really interested in what other people can contribute and have a real faith in that and not want to hog the limelight all yourself.

Getting the Knowledge Into the Hands of the Right People!

It's important to get the right kind of knowledge into the hands of the people who need it because if you can get knowledge into the hands of the right people they can solve the problems rather than depending on other people to solve the problems which makes them more dependent on more hierarchical and inequalities and so on and so forth. Interestingly, at the root of Toyota's lean production system is the idea that the shop floor worker should be able to correct the fault there and then. And if you take that as a principle of a lean system, that you need the knowledge as close as possible to where the problem is not a long way away because that becomes inefficient, then actually then you think how important it is for lean systems because they're very low waste and very high quality. Then what would a socially-lean system be, it would be a system in which relevant knowledge was in the hands of people in a much more distributed way rather than being hoarded or controlled in institutions or professions or what have you, fundamentally, that's why it matters.

So if you're thinking about the challenge of maternal death in childbirth, why millions of women still die in childbirth and why millions of babies die before and after birth, that's because many of these places don't have health systems where the knowledge is available where it's needed.

Which Kind of Economical System is Needed

It's clear that what we're in is in one way is an economic system that more and more people want to be part of because millions and millions of people are moving to cities and they're moving to cities to be part of markets and economic systems. So in one sense it's hugely successful. In another sense it encourages huge aspiration and choice and desire and people uproot themselves to be able to afford better consumer durables and so on and so forth. So in one sense capitalism is still hugely powerful and all the rest of it. In another sense it has really reluctant acceptance in some ways I think. It is capable of being deeply self-interested and destructive. It rewards often predatory behavior. And at the same time as including people, come and consume, come and work, it can kind of disable people and there are in the developed world, in Europe and America, there are literally millions and millions and millions of people on modest incomes who haven't seen their incomes rise and haven't been beneficiaries of growth.

So even if we come out of the current recession crisis into growth the fact is that if you're on 25,000 pounds or 40,000 dollars actually you're not going to benefit very much because actually people who are richer are going to benefit. And so fundamentally we've got a really powerful but really broken model and so we will need to reinvent it in a way that means that it's less destructive, more stable, more inclusive, less environmentally destructive. And that that is the big challenge in that people are going to have to learn how to make money and create growth but without being so unstable and destructive I suppose.

How Can Corporations Keep Up With the Change?

They need to be open to the world and they need to be constantly learning. They need to be constantly experimenting with people out in the world and they need to be setting themselves big ambitions and big challenges and to use fewer resources and to find more inclusive ways of working. And I think if you get organizations which accept big challenges that don't just want to do what they've always been doing and carry on as if everything's fine then I think those organizations will actually succeed. I think fundamentally people want companies that help them live more successful lives basically. They reward companies who are helping them live more successfully rather than companies who are only interested in their own profits fundamentally. And that I think is the key thing. Are you really trying to help other people live more successfully or are you just really helping yourself?

CollaborativeSociety.org is a site which explores the thinking of researchers, academicians and thought-leaders on the topic of collaboration, among other things. Thanks to Alfred Birkegaard and Katja Carlsen for providing the video content. The contribution of The Collaboration Project is these transcripts.